The Big Sweep

I get excited when street sweeping day arrives in my neighborhood. As I get older, fewer things bring out a childlike giddiness in me, but the appearance of those vehicles on my street does.

I love seeing functional public works in action. And I like when things are clean. On my street, most of the debris that collects along the curb is from trees, but mud, standing water, and pieces of trash also pile up.

When the street sweepers come to clear it all away, the neighborhood feels refreshed and renewed.

When I lived in New York City, street sweeping was a source of anxiety. The vehicles came four times a week, and if my car was parked on a side of the street that was getting cleaned, I would have to do what I called “the alternate side shuffle.”

This meant sitting in my car within the appointed 90-minute window when the cleaning might occur, waiting for the sweeper to arrive, pulling out into traffic when it did arrive to allow the vehicle to clean the debris off the curb, then backing into the spot I had just vacated — all while negotiating the regular flow of traffic and also battling other parkers for a few feet of curb space.

This process was the trade-off for not spending $500 a month to keep my car in a garage. If you have a car in Manhattan long enough, you get used to it. But for newbies, the alternate side shuffle can be a traumatic experience.

In New Haven, the street parking life is simpler. The sweepers come twice a month, and finding parking on those days is generally easy. (Though sometimes someone will ignore the no parking signs and leave their car in front of my house. Yes, they get a $100 fine, but I’m left with a messy curb for another month.)

I always get a small thrill when I see those sweepers going by. And with so many upsetting things happening in the world right now, taking a moment to appreciate even the most mundane occurrence feels like a worthwhile act.

The Best…

…Series I Watched This Week

Reservation Dogs — Co-created by Sterlin Harjo and Taika Waititi

Streaming on Hulu

Here’s how much I enjoyed the series Reservation Dogs, which just finished its 3-season run on Hulu: immediately after watching the finale, I went back to the very first episode and re-watched the entire series.

The show’s primary focus is on four Indigenous teenagers who live on a reservation in Oklahoma. When the series begins, we see them — Bear (played by D’Pharaoh Woon-A-Tai), Elora Danan (Devery Jacobs), Willie Jack (Paulina Alexis), and Cheese (Lane Factor) — amateurishly stealing a delivery truck and selling it for cash at a salvage yard.

On the surface, they do this for the money. They’re saving up so they can all escape their community and move to California, a plan first hatched by their friend Daniel.

The idea of this trip gives them all purpose, something to look forward to, but it’s really just a stand-in for their grief — Daniel died by suicide a year before the first episode takes place.

As the series unfolds, each of the four kids has to reckon with their grief, their guilt over Daniel’s death, the impact of their behavior on their families and friends, and what it means to be a member of a small but resilient community.

Co-created by Sterlin Harjo and Taika Waititi, the show does a beautiful job of showing the kids’ respective evolutions over three seasons. It also widens its scope to look at the lives of their parents’ and grandparents’ generations, while linking them all to the deeper history of North America’s Indigenous people.

When I think of Reservation Dogs, I’m reminded of how funny it is (there are so many recurring jokes), how intimate it is, how you come to care about the characters so much. The show is hilarious, yet melancholy hangs over nearly every moment. The sadness, though, is not overwrought or overwhelming. And I loved the way the show integrates magical realism while never fully losing its grounding in reality.

Reservation Dogs begins with four angry, sad kids acting out, hurting themselves and everyone around them. The story it goes on to tell, about the importance of people within a community taking care of each other, has resonance for us all.

…Movie I Watched This Week

Theater Camp (2023) — Directed by Molly Gordon and Nick Lieberman

Streaming with subscription on Hulu; available for rent on other platforms

From age 11 to 13, I spent my summers in Maine at music camp. No, not band camp. Music camp.

At Camp Encore/Coda (“for musical boys and girls”), I played alto sax, clarinet, and jazz piano. Over those three summers, I participated in a variety orchestras, wind ensembles, jazz bands, and jazz combos. I also performed in a few plays. (And I played on several sports teams, where I was one of the best athletes — it was an “in the land of the dorks, the coordinated boy is king” kind of thing.)

All of which is to say that I was around a lot of artsy kids, and we all grew accustomed to the following routine: audition, get placed in a group, rehearse, perform.

Because of this experience, I was intrigued when I heard about the movie Theater Camp. The film is a mostly-improvised mockumentary set at a fictional summer camp in the Adirondacks (the camp is called AdirondACTS), where eccentrically enthusiastic teachers train their precocious charges in the various arts of the stage. (The film’s dramatic backdrop is whether the camp can survive its financial challenges while being run by the incapacitated owner’s idiot son.)

I missed the movie when it was out last summer, and my expectations were dampened when a few family members — including two fellow Camp Encore/Coda alums — panned it. But with a running time of 94 minutes, I decided to roll the dice and stream it this week.

And… I liked it! It’s the movie Christopher Guest would have made if he had gone to theater camp. Although he didn’t, the film’s stars, Molly Gordon and Ben Platt, did (they co-wrote the script with Nick Lieberman and Noah Galvin). So they know very well who their characters are, exaggerating their quirkiness for maximum awkwardness. Everyone in the film is skewered in one way or another, but it’s done with great love and affection.

Though Encore/Coda was not nearly as ridiculous as AdirondACTS, watching the movie did spark some fond memories of my time auditioning, rehearsing, and performing at music camp. No, not band camp. Music camp.

…Book I Read This Week

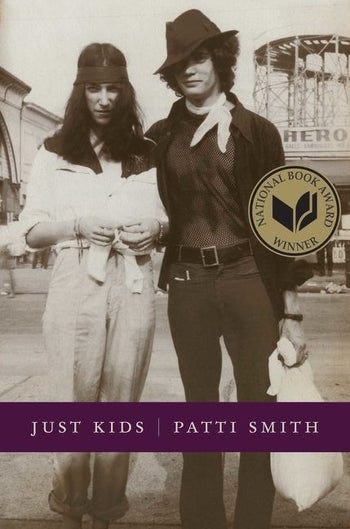

Just Kids (HarperCollins Publishers, 2010) — By Patti Smith

Until recently, my awareness of Patti Smith was largely confined to knowing that she had collaborated with Bruce Springsteen on the song “Because the Night,” which, in 1978, became her biggest hit.

The one other thing I knew was that she had written a renowned memoir called Just Kids about her relationship with the artist Robert Mapplethorpe.

Because of its reputation, I picked up a copy of the book about six months ago but only cracked it this week. Once I got going, though, I plowed through the final 200 pages in one sitting — I just didn’t want to do anything else.

The book, published in 2010, largely concentrates on Smith’s life in her twenties, after she drops out of college and moves from South Jersey to Manhattan. There, she meets Mapplethorpe. As almost literal starving artists, they become each other’s subject and muse. Lovers (for a time). Protectors. Friends.

In fascinating and perceptive detail, Smith documents their disparate approaches to being artists. Robert is cocky and prolific, sure that he’s going to become successful and famous, even when no one else seems to agree. Patti, while working a day job to pay the pair’s expenses, often feels lost, unsure of where her creative life is heading.

Robert indeed becomes a celebrated photographer, but Patti’s is the more interesting story: after years of creative wandering, her surprising discovery that she belongs on stage, fronting a rock band, is an incredibly satisfying journey to follow.

Part of what makes the book remarkable is the level of detail Smith employs in her storytelling. Her prose evokes clear images of barely-inhabitable apartments, outlandish characters, and reams of artwork.

She clearly kept diaries at the time, and I found myself wishing I had started keeping a journal when I was younger. Not necessarily because I’d like material for a memoir, but just because I’ve forgotten so much of what happened to and around me. Thanks to Smith’s apparently copious notes, she has no such issue.

As a result, Just Kids comes across as an engaging love letter to Mapplethorpe, to Manhattan’s avant garde art world of the late-1960s and early-’70s, to Smith’s younger self, and, above all, to the artist’s life.